Community Policing & Peacebuilding Processes

Last Updated: April 7, 2009

The governance of security in weak or failing states

In general, the demand for security often exceeds the state's capacity to provide it. Although state strength is relative, it is often measured on a range according to the states ability and willingness to provide political goods associated with statehood such as physical security, legitimate political institutions, economic management, and social welfare, and its capacity to control its territory. In weak, failing or collapsed states the threats to security are more amplified. Their inherent structural weakness often causes of the proliferation and expansion of private security actors. Researcher Anthony Minnaar remarks that "One of the main stumbling blocks to establishing partnership is police fear of a loss of autonomy and the implied association of private security personnel with private interests, which would lead to contradictory demands on activities. Nevertheless, the partnership approach gained momentum in developed countries in the mid-1990s, linked as it was to the development of community policing and the emphasis on community safety and crime prevention. The narrow interpretation of crime prevention as the sole preserve and responsibility of the (public/state) police also became obsolete."1Weak or failing states and insecurity

Weak or failing states have traditionally focused more on internal than external security threats. The legacies of colonialism, the process of state formation, and international norms favoring juridical statehood2 have contributed to explaining why there is such a concern for internal security in weak or failing states. Under such conditions, the state and its institutions may not be able to guarantee the safety and security to all its citizens. Public security providers in weak or failing states tend to lack accountability. They often resort to corrupt practices in order to supplement their inadequate salaries or are simply spread too thin and lack core resources to be able to perform the duties adequately. In some instances, there is no distinction between military and police institutions since both are directed against or concerned with internal security threats to the regime.3The decline of state policing and the proliferation of other types of security actors

In post-conflict environments, changing the political culture surrounding public security is already difficult, but the police and other non-military security forces that emerge from conflict situations are often perceived by local communities as partial actors. For instance, in Albania, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) project on Security Sector Reform (SSR) which focuses on community policing, police transparency and accountability has run into numerous obstacles due to the continued widespread police abuse and past political control of the police in conjunction with corruption and low effectiveness.4 As security expert, Timothy Donais remarks, "domestic forces are almost inevitably drawn into ongoing and unresolved political struggles and used as instruments of political power."5 The multiplicity of actors offering security services has challenged traditional notions of sovereignty and security governance and raised questions about the appropriate kinds of mechanisms to reform policing organizations.Criminologists David Bayley and Clifford Shearing have argued that a multilateralization of policing, in which a variety of different institutional forms"be it public, private, non-profit, for profit, formal and informal, and hybrids"have cropped up to deliver policing services. 6 This has been a far cry from the type of policing conceived by Sir Robert Peel when he established public policing as an organized professional establishment in 1829. In addition, criminal justice scholar Les Johnston has also questioned the sacrosanct belief that the state governed policing, especially after the rise of transnational private policing during the latter half of the 20th century.7 Johnston has cited the examples of Sandline International which was involved during the conflicts in Papua New Guinea and Sierra Leone in the 1990s, Executive Outcomes, which has operated in support of the armed forces, law enforcement agencies, and private corporations in many parts of Africa, and Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI), which has been involved in numerous operations in Africa and Latin America since 1987. While Bayley, Shearing, and Johnston have argued that the fragmentation of policing has moved policing away from the state, policing expert Bruce Baker has asserted that at least in Africa, the proliferation of security actors has taken place within the boundaries of state initiation or at the minimum with state influence and approval.8

The case of Swaziland illustrates Baker's point in terms of the tensions among the different security actors within the state: public security, private security actors, and community policing. Hamilton Sipho Simelane in his study of Swaziland notes that, "Presently, there is a precarious balance of power between public security as represented by the RSP [Royal Swaziland Police] and the USDF [Umbutfo Swaziland Defence Force]; PSCs [private security companies] and community police. At the moment the rivalry between the three is not highly pronounced but is bound to grow and create social tensions. The state has made several attempts to bring community police forums under the arm of the RSP, but this has had very little success as most rural communities are showing preference for community police. This conflict has not reached crisis levels because public security forces still have an upper hand as they enjoy government funding, while such funding is still denied for Community Police Forums."9

[Back to Top]

Community policing and security sector reform

Community policing is sometimes encouraged by donors on an ad hoc basis as part of police reform initiatives under security sector refrom (SSR). For instance in Macedonia, the concept was encouraged donors in an attempt to reclaim and stabilize northern areas of the country where the National Liberation Army (NLA) insurgency was the strongest. Joint patrols of equal numbers of ethnic Albanian and Macedonian police officers, typically accompanied by international police monitors were implemented in this region.10In Sierra Leone, Partnership Boards were established by the Sierra Leonean Police (SLP) when they embraced the concept of Local-Needs Policing after the war. The Partnership Boards were chaired by civilians and included representatives from important groups and interests in the locality. However, cooperation between the local community and the SLP was tenuous and the extent to which local community input was taken into consideration in improving state policing was minimal.11

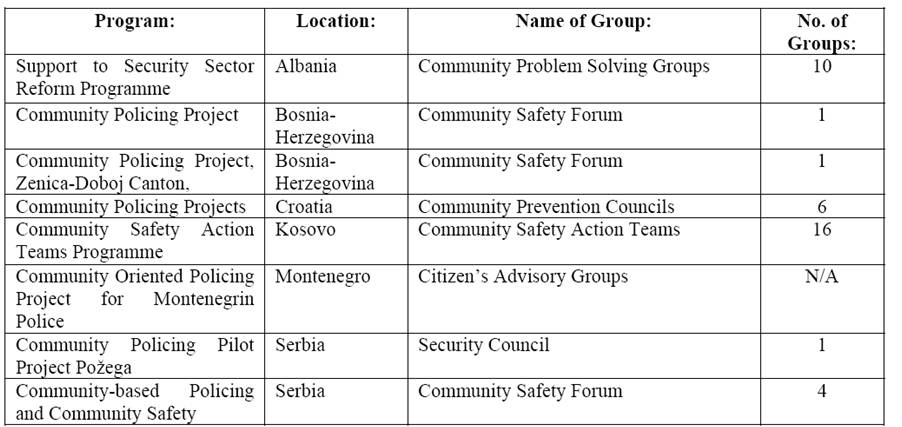

A study on UNDPs community policing practices in Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Romania, and Serbia as part of the Support to Security Sector Reform (SSSR) found that two types of community policing emerged"one that was more focused on police activities and another that was more focused on the community.12 Community policing that was more police-oriented emphasized the training of police in the philosophy and practice of community policing. They would then work with the community to identify and resolve local issues. In contrast, community policing that was more community-oriented involved the police working with the community to identify local problems. These programs at times lacked substantial training.

Community Policing in Eastern Europe

Source: Sean DeBlieck, The Critical Link: Community Policing Practices in Southeastern Europe: UNDP Albania/SSSR Programme. (UNDP Albania, February 2007).

Nevertheless, Groenewald and Peake note that "External actors pick and choose which parts of security sector reform (SSR) they carry out without necessarily seeing how these elements are linked and interrelated. Although at a policy level, the police are considered an integral element of the security sector, this synergy between the two is rare at the level of implementation. For many donors, SSR remains a primarily military concern, deprioritizing policing. Policing is also sometimes in a different institutional 'silo,' which presents an institutional barrier to actual coordination. Greater synergy between the reform processes towards the various institutions that make up the security sector would be beneficial."13

Although policing reform is generally included in the rhetoric of SSR, the majority of activities still remain in the realm of military and intelligence services, with less attention paid to border control agencies and the police. At times, police reforms are conducted in isolation of other reforms process such as the judiciary and penal system. However, the reform of law enforcement organizations have been increasingly regarded as a necessary component to build trust in communities. As Thorsten Stodiek comments on the creation of multi-ethnic police forces, "Even if the police behave appropriately and protect the rights of all citizens in an unbiased way, some ethnic groups may need more time to gain confidence. For this reason comprehensive and long-lasting confidence-building programmes such as 'community policing' are necessary."14

[Back to Top]

Community policing, the rule of law, and human rights

Human rights violations commited by police officials and non-observance of the rule of law have contributed to reinforcing the perception of mistrust amongst some local communities. Effective police reforms need to be linked to other criminal justice institutions. 15 Instilling democratic norms in police institutions mean that police actions must therefore be governed by the rule of law rather than by directions given arbitrarily by particular regims and their members.16At the same time, upholding the rule of law may conflict with the responsibility to protect human rights, especially if the law requires police institutions to act in an arbitrary and repressive manner. Futhermore, in order for police to act according to human rights standards it is necessary for them to have received extensive and practical training. Many post-transition societies were unaccustomed to security systems founded on human rights and citizen service. Human rights organizations had focused on denouncing abuses and were poorly equipped to articulate demands for citizen-oriented policing.17 For instance, in Haiti, there was no effective system to administer justice, uphold the rule of law and provide impartial protection of human rights. Earlier human rights abuses commited between 1991 to 1994 by the Haitian National Police were still left unaddressed and new reports on the excessive use of force by police officers and extrajudicial executions persisted as of 2006.18 Human rights experts of the International Civilian Mission in Haiti (MICIVIH) initially designed a curriculum for the police academy that incorporated a topic called, "human dignity" that was unrelated the realities of Haitian policing and ambiguous on human rights issues.19 Furthermore, human rights activitists tend to view the police soley as perpetrators of human rights violations, whereas the police often tend to feel that human rights activitist are in alliance with criminals or political opposition groups, and part of the problem.20 The European Platform for Policing and Human Rights has developed a basic template to help human rights non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and police services develop joint-projects to foster more cooperation.21

Some scholars advocate that police reform emphasize "the rule of law and long-term justice and security, rather than short-term order. It encompasses the human-rights view to an extent, but goes beyond it with a focus on institutional development. Using terminology like police reform, rule of law and justice reform, donor agencies dedicated to judicial reform and the rule of law, and many academic analysts of police reform, are the best examples of this more variegated category. Development agencies, initially drawing principally on economic rationales for police reform, have increasingly embraced this perspective as well, drawing on a more holistic relationship between security, development and democracy, including attention to policing."22 Go to Justice and Rule of Law and Human Rights Promotion and Protection

[Back to Top]

Community policing, development, and poverty reduction

Several donor agencies and governments consider community policing an integral component that can contribute to a wider poverty reduction strategy. This approach falls under the broader attempts to link security sector initiatives with development and poverty reduction initiatives. Peacebuilding scholar Charles Call notes that, "Some development agencies and international financial institutions have recently overcome longstanding resistance to involvement with armed institutions and have supported demobilisation and police-reform projects. Under the rubric of 'security sector reform', these projects reflect interest in enhancing the environment for economic development, removing impediments to foreign investment, and reducing the costs of crime and violence. For instance, the Inter-American Development Bank has cited the social and health costs of violence as reasons for expanding its police development projects. Treating the new 'security sector' like other economic sectors, such as health and agriculture, allowed international organisations to press developing countries to reduce exorbitant levels of military expenditure. These developments have opened the way for police-reform initiatives."23The incorporation of policing activities in the development agenda is predicated on the assumption that high levels of crime and corruption stifle development in a community - businesses become victims of crime, commercial activities (including those in the informal sector) are interrupted, and foreign investment leaves. However, Phillipe Le Billion has argued that although the consequences of corruption are overwhelmingly negative, it may help at least in the short-term secure some degree of political, economic, and social stability by buying out "peace spoilers" or authorizing illegal yet licit economic activities sustaining local livelihoods.24 In addition, the poor and marginalized often lack access to political or social structures and are unlikely to have any influence over politics and the programs that affect their daily lives. Therefore, community policing initiatives attempt to make peoples access to justice more accessible, regardless of their social or economic status by bringing law enforcement organizations closer to the population.25

While overlapping economic development activities with security sector activities such as police reform might be mutually beneficial, more research needs to be done in this area to understand the root causes of crime and the precise links between economic development and security issues.

Go to Economic Recovery

[Back to Top]

Community policing and SALW control

Reducing the level of insecurity and improving safety in a community is one of the primary objectives of community policing. However, citizens will only be willing to hand over illicit firearms in their possession if they perceive an improvement in the public safety and security and if they have a certain degree of trust in the police and other law enforcement agencies. Community policing is regarded by many donors as a gateway to help build confidence and improve the relationship between local law enforcement officials and the community.In South Africa, for example, a number of community policing initiatives have been undermined by the level of firearms violence. A report by Amnesty International states that, "In 1999, about 25,000 people were murdered, well over half with firearms. Some of the victims were police officers. Most police are authorized to carry firearms despite a lack of in-service training. In addition, many tens of thousands of civilians own firearms legally. The South African parliament began to consider tightening gun controls, but the problem of gun violence is well entrenched." 26

The scholar Bruce Baker reminds us that, "It is within this gun culture, where there are high levels of violent crime and where people want to protect themselves with weapons, that non-state policing operates. Not surprisingly, it commonly allows its agents to carry instruments of coercion, whether chemical sprays, handcuffs, batons and licensed pistols in the case of commercial security firms, or a variety of weapons in the case of informal non-state policing. Even in the commercial and 'responsible' citizen group sector, the training is minimal and the guidelines for use are basic. In the autonomous citizen sector, of course, there are very few restraints at all. With the government doing very little to tackle the ownership and use of firearms and other weapons generally and their use by non-state policing groups in particular, they are freely used in the course of nonstate policing with little supervision."27

SALW control activities are not always linked to police reform initiatives; somestimes the two activities occur simultaneously in isolation on each other. There have been more increasing attempts to link or find synergies between SALW control initiatives and DDR programs, especially (community-based) weapons collection programs and disarmament and demobilization projects. Policing reform has been a rather neglected area of security sector reform that has been addressed on an ad hoc basis. Some analysts see the need to reduce the number of firearms in circulation as a way to improve public security, and thus training in the management of safeguarding police stockpiles, keeping accurate inventories of weapons and appropriate weapons handling need to be reinforced.28

[Back to Top]

Intersecting gender with community policing

The gender dimensions of policing are increasing being taken into consideration. UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) has noted that the increased representation of women in the police forces is an important part of gender-sensitive police reform.29 The recruitment of more women in the police force does not automatically guarantee a more gender-sensitive police force, especially if the overall police system and training still reinforces practices that discriminate against women. Therefore it is necessary in post-conflict contexts to seek to attract large numbers of women to improve the gender parity. Moreover, recruitment drives targeting women should not promoted gendered divisions of labor and power that relegate women to the lowest ranks.30 For example, in Afghanistan, the low status and military character of the police are discouraging factors for women. However, given the separation of sexes in Afghanistan, they are more qualified to handle family and domestic cases and are vital to deal with female suspects. Efforts to attract more women in the police forces have included the creation of an all female dormitory at the Kabul Police Academy and training for non-commissioned officers on a regional basis in Baghland for women unable to live away from their families for long periods of time.31In Sierra Leone, women recruited for community policing work directly with other women through the Local Police Partnership Boards, which has help to include women in the decision-making processes within their communities and also improve police response to crimes against women. Due to the countrys high rate of sexual and gender-based violence, women participating in community policing initiatives helped bring a more gender-sensitive approach to police reform and peacebuilding activities.32

Experts note that women's access to security and justice is important since customary law and religious practicies often greatly affect womens lives and status.33 The UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO)'s Guidelines for Integrating Gender Perspectives in National Police and Law Enforcement Agencies states that, "Women must be involved in all consultations for designing community policing policies, to ensure that their security priorities are reflected. For example, women may have a different view on what crimes need priority attention, which parts of the neighborhood may be particularly dangerous, and what approaches are most likely to be successful in preventing crime and providing security to the population. Women should be seen as agents in planning and not merely as beneficiaries of new community policing practices."34

Although there are studies on the overall topic of gender and police reform, there is a paucity of analysis on the role of gender with a specific focus on community policing in post-conflict peacebuilding. More research needs to be conducted on how local police can serve the community more effectively and ensure that the needs of women, men, girls and boys are addressed.

Go to Empowerment: Women and Gender Issues

1. Anthony Minnar, "Oversight and monitoring of non-state/private policing: The private security practitioners in South Africa," in Private Security in Africa: Manifestations, Challenges and Regulations, by Sabelo Gumedze (ed.). ISS Monograph Series 139 (2007), 143.

2. The term juridical statehood in international law is an entity that is recognized by other states as a state, even though it does not have a monopoly on the legitimate use of force over a territory. See: Robert Jackson and Carl Rosberg, "Why Africa's Weak States Persist: The Empirical and The Juridical in Statehood," World Politics, Vol. 35, No. 1 (1982); and Max Weber, The Profession and Vocation of Politics,in Political Writings, ed. Peter Lassman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

3. Charles Call and Michael Barnett, "Looking for a Few Good Cops: Peacekeeping , Peacebuilding and the UN Civilian Police," International Peacekeeping, Vol. 6, No. 4 (Winter 1999): 45.

4.Eirin Mobekk, "Police Reform in South East Europe: An Analysis of the Stability Pact Self-Assessment Studies," in Defence and Security Sector Governance and Reform in South East Europe Self-Assessment Studies: Regional Perspective, ed. Eden Cole, Timothy Donais and Philipp H. Fluri (Geneva: Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF), 2003), 6.

5. Donais, "Back to Square One: The Politics of Police Reform in Haiti,".

6. D. Bayley and C. Shearing, "The Future of Policing," Law and Society Review, Vol. 30, No. 3 (1996); and D. Bayley and C. Shearing. The New Structure of Policing: Description, Conceptualization and Research Agenda. (Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Justice, 2001).

7. Les Johnston, "Transnational Private Policing: The Impact of Global Commercial Security," in Issues in Transnational Policing, J. Sheptycki (London: Routledge, 2000).

8. Bruce Baker, "Post-conflict Policing: Lessons from Uganda 18 Years On," Journal of Humanitarian Assistance (July 12,2004); Bruce Baker, "Who Do People Turn to for Policing in Sierra Leone?" Journal of Contemporary African Studies, Vol. 23, No. 3 (September 2005).

9. Hamilton Sipho Simelane, "The State, Security Dilemma, and the Development of the Private Security Sector in Swaziland," in Private Security in Africa: Manifestations, Challenges and Regulations, by Sabelo Gumedze (ed.). ISS Monograph Series 139 (2007), 164.

10. Gordon Peake, Policing the peace: Police Reform Experiences in Kosovo, Southern Serbia and Macedonia (London: Saferworld, 25 June 2004), 36.

11. Bruce Baker, "Who Do People Turn to for Policing in Sierra Leone?" Journal of Contemporary African Studies, Vol. 23, No. 3 (September 2005): 378.

12. Sean DeBlieck, "The Critical Link: Community Policing Practices in Southeastern Europe: UNDP Albania/SSSR Programme" (UNDP Albania, February 2007).

13. Hesta Groenewald and Gordon Peake, Policing Reform through Community-Based Policing: Philosophy and Guidelines for Implementation (New York: International Peace Academy and Saferworld, September 2004), 3.

14. Thorsten Stodiek, "The OSCE and the Creation of Multi-Ethnic Police Forces in the Balkans" (CORE Working Paper 14, Centre for OSCE Research, Hamburg), 8.

15. Groenewald and Peake, Policing Reform through Community-Based Policing, 3.

16. David Bayley, "Democratizing the Police Abroad: What to Do and How to Do It" (Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, U.S Department of Justice, 2001).

17. Charles Call, "Pinball and Punctuated Equilibrium: The Birth of a Democratic Policing Norm?" (Paper for the Annual conference of the International Studies Association in Los Angeles, CA, March 16, 2000), 4-5.

18. Amnesty International, "2006 Annual Report for Haiti," in Amnesty International Report 2006: The State of the Worlds Human Rights (London: Amnesty International Publications, 2006).

19. William G. ONeill, "Police Reform and Human Rights," (A HURIST document, UNDP, New York, 2004).

20. Cristina Sganga, "Human Rights Education - As a Tool for the Reform of the Police," Journal of Social Science Education, No. 1 (2006).

21. See: European Platform for Policing and Human Rights, "Police and NGOs: Why and how human rights NGOs and police services can and should work together "(European Platform for Policing and Human Rights, December 2004).

22. Charles T. Call. "Competing Donor Approaches to Post-Conflict Police Reform," Journal of Conflict, Security and Development, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring 2002): 105-106.

23. Call, "Competing Donor Approaches," 105.

24. Phillippe Le Billion, "Thought Piece: What is the impact: Effects of Corruption in Post-Conflict." Paper for The Nexus: Corruptions, Conflict & Peacebuilding Collogquium, Tufts University (April 12 and 13, 2007).

25. Groenewald and Peake, Policing Reform through Community-Based Policing, 3-4.

26. Amnesty International. Policing to protect human rights: A survey of police practice in countries of the Southern African Development Community, 1997-2002 (London: Amnesty International Publications, 2002), Chapter 6.

27. Bruce Baker, "Living with non-state policing in South Africa: the issues and dilemmas," Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 40, No. 1 (2002): 50.

28. South Eastern Europe Clearinghouse for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons, Philosophy and principles of community-based policing (Belgrade: SEESAC, 2003), 5.

29. UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) and UN Development Programme (UNDP), Policy Briefing Paper: Gender Sensitive Police Reform in Post Conflict Societies (New York: UNIFEM and UNDP, October 2007).

30. Ibid.

31. International Crisis Group, "Reforming Afghanistans Police" (Asia Report No. 138, International Crisis Group, August 30, 2007), 11.

32. Centre for Development and Security Analysis (CEDSA), "Women in Security" (Peace, Security and Development Update, issue 3, CEDSA, March 2008).

33.Hesta Groenewald and Gordon Peake, Policing Reform through Community-Based Policing: Philosophy and Guidelines for Implementation (New York: International Peace Academy and Saferworld, September 2004).

34. UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Guidelines for Integrating Gender Perspectives in National Police and Law Enforcement Agencies (New York: United Nations, 14 April 2008), 7.